Tracking Bugs¶

So far, we have assumed that failures would be discovered and fixed by a single programmer during development. But what if the user who discovers a bug is different from the developer who eventually fixes it? In this case, users have to report bugs, and one needs to ensure that reported bugs are systematically tracked. This is the job of dedicated bug tracking systems, which we will discuss (and demo) in this chapter.

Prerequisites

- You should have read the Introduction to Debugging.

# ignore

if 'CI' in os.environ:

# Can't run this in our continuous environment,

# since it can't run a headless Web browser

sys.exit(0)

# ignore

#

# WARNING: Unlike the other chapters in this book,

# this chapter should NOT BE RUN AS A NOTEBOOK:

#

# * It will delete ALL data from an existing

# local _Redmine_ installation.

# * It will create new users and databases in an existing

# local _MySQL_ installation.

#

# The only reason to run this notebook is to create the book chapter,

# which is the task of Andreas Zeller (and possibly some translators).

# If you are not Andreas, you should exactly know what you are doing.

assert os.getenv('USER') == 'zeller'

Reporting Issues¶

So far, we have always assumed an environment in which software failures would be discovered by the very developers responsible for the code – that is, failures discovered (and fixed) during development. However, failures can also be discovered by third parties, such as

- Testers whose job it is to test the code of developers

- Other developers using the code

- Users running the code as it is in production

In all these cases, developers need to be informed about the fact that the program failed; if they won't know that a bug exists, it will be hard to fix it. This means that we have to set up mechanisms for reporting bugs – manual ones and/or automated ones.

What Goes in a Bug Report?¶

Let us start with the information a developer requires to fix a bug. In a 2008 study \cite{Bettenburg2008}, Bettenburg et al. asked 872 developers from the Apache, Eclipse, and Mozilla projects to complete a survey on the most important information they need. From top to bottom, these were as follows:

Steps to Reproduce (83%)¶

This is a list of steps by which the failure would be reproduced. For instance:

- I started the program using

$ python Debugger.py my_code.py.- Then, at the

(debugger)prompt, I enteredrunand pressed the ENTER key.

The easier it will be for the developer to reproduce the bug, the higher the chances it will be effectively fixed. Reducing the steps to those relevant to reproduce the bug can be helpful. But at the same time, the main problem experienced by developers as it comes to bug reports is incomplete information, and this especially applies to the steps to reproduce.

Stack Traces (57%)¶

These give hints on which parts of the code were active at the moment the failure occurred.

I got this stack trace:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "Debugger.py", line 2, in <module>

handle_command("run")

File "Debugger.py", line 3, in handle_command

scope = s.index(" in ")

ValueError: substring not found (expected)

Even though stack traces are useful, they are seldom reported by regular users, as they are difficult to obtain (or to find if included in log files). Automated crash reports (see below), however, frequently include them.

Test Cases (51%)¶

Test cases that reproduce the bug are also seen as important:

I can reproduce the bug using the following code:

import Debugger

Debugger.handle_command("run")

Non-developers hardly ever report test cases.

Observed Behavior (33%)¶

What the bug reporter observed as a failure.

The program crashed with a

ValueError.

In many cases, this mimics the stack trace or the steps to reproduce the bug.

Screenshots (26%)¶

Screenshots can further illustrate the failure.

Here is a screenshot of the

Debuggerfailing in Jupyter.

Screenshots are helpful for certain bugs, such as GUI errors.

Expected Behavior (22%)¶

What the bug reporter expected instead.

I expected the program not to crash.

Configuration Information (< 12%)¶

Perhaps surprisingly, the information that was seen as least relevant for developers was:

- Version (12%)

- Build information (8%)

- Product (5%)

- Operating system (4%)

- Component (3%)

- Hardware (0%)

The relative low importance of these fields may be surprising as entering them is usually mandated in bug report forms. However, in \cite{Bettenburg2008}, developers stated that

[Operating System] fields are rarely needed as most [of] our bugs are usually found on all platforms.

This not meant to be read as these fields being totally irrelevant, as, of course, there can be bugs that occur only on specific platforms. Also, if a bug is reported for an older version, but is known to be fixed in a more current version, a simple resolution would be to ask the user to upgrade to the fixed version.

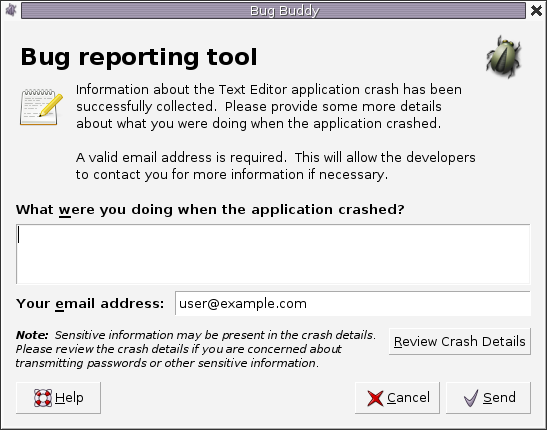

Reporting Crashes Automatically¶

If a program crashes, it can be a good idea to have it automatically report the failure to developers. A common practice is to have a crashing program show a bug report dialog allowing the user to report the crash to the vendor. The user is typically asked to provide additional details on how the failure came to be, and the crash report would be sent directly to the vendor's database:

The automatic report typically includes a stack trace and configuration information. These two do not reveal too many sensitive details about the user, yet already can help a lot in fixing a bug. In the interest of transparency, the user should be able to inspect all information sent to the vendor.

Besides stack traces and configuration information, such crash reporters could, of course, collect much more - say the data the program operated on, logs, recorded steps to reproduce, or automatically recorded screenshots. However, all of these will likely include sensitive information; and despite their potential usefulness, it is typically better to not collect them in the first place.

Effective Issue Reporting¶

When writing an issue report, it is important to look at it from the developer's perspective. Developers not only require information on how to reproduce the bug; they also want to work effectively and efficiently. The following aspects will all help developers with that:

- Have a concise summary. A good summary should quickly and uniquely identify a bug. Make it easy to understand such that the reader can know if the bug has been reported and/or fixed.

- Be clear and concise. Provide necessary information (as shown above) and avoid any extras. Use meaningful sentences and simple words. Structure the report into enumerations and bullet lists.

- Do not assume context. Make no assumption that the developer knows all about your bug. Find out whether similar issues have been reported before and reference them.

- Avoid commanding tones. Developers enjoy autonomy in their work, and coming across as too authoritative hurts morale.

- Avoid sarcasm. Same as above. If you think you can get a volunteer to fix a bug in an open source program for you with sarcasm or commands – good luck with that.

- Do not assume mistakes. Do not assume some developer (or anyone) has made a mistake. In many cases, issues can be resolved on your side.

- One issue per report. If you have multiple issues, split them in multiple reports; this makes it easier to process them.

An Issue Tracker¶

At the developer's end, all issues reported need to be tracked – that is, they have to be registered, they have to be checked, and of course, they have to be addressed. This process takes place via dedicated database systems, so-called bug tracking systems.

The purposes of an issue tracking system include

- to collect and store all issue reports;

- to check the status of issues at all times; and

- to organize the debugging and development process.

Let us illustrate how these steps work, using the popular Redmine issue tracking system.

This is what the Redmine tracker starts with:

# ignore

redmine_gui.get(redmine_url + '/login')

screenshot(redmine_gui)

After we login, we see our account:

# ignore

redmine_gui.find_element(By.ID, "username").send_keys("admin")

redmine_gui.find_element(By.ID, "password").send_keys("admin001")

redmine_gui.find_element(By.NAME, "login").click()

screenshot(redmine_gui)

We start with a list of projects.

# ignore

redmine_gui.get(redmine_url + '/projects')

screenshot(redmine_gui)

Let us choose the (one) "debuggingbook" project.

# ignore

redmine_gui.get(redmine_url + '/projects/debuggingbook')

screenshot(redmine_gui)

Reporting an Issue¶

The most basic task of a bug tracker is to report bugs. However, a bug tracker is a bit more general than just bugs – it can also track feature requests, support requests, and more. These are all summarized under the term "issue".

Let us take the role of a bug reporter – pardon, an issue reporter – and report an issue. We can do this right from the Redmine menu.

# ignore

redmine_gui.get(redmine_url + '/issues/new')

screenshot(redmine_gui)

Let's give our bug a name:

issue_title = "Does not render correctly on Nokia Communicator"

issue_description = \

"""The Debugging Book does not render correctly on the Nokia Communicator 9000.

Steps to reproduce:

1. On the Nokia, go to "https://debuggingbook.org/"

2. From the menu on top, select the chapter "Tracking Origins".

3. Scroll down to a place where a graph is supposed to be shown.

4. Instead of the graph, only a blank space is displayed.

How to fix:

* The graphs seem to come as SVG elements, but the Nokia Communicator does not support SVG rendering. Render them as JPEGs instead.

"""

# ignore

redmine_gui.get(redmine_url + '/issues/new')

redmine_gui.find_element(By.ID, 'issue_subject').send_keys(issue_title)

redmine_gui.find_element(By.ID, 'issue_description').send_keys(issue_description)

screenshot(redmine_gui)

# ignore

redmine_gui.find_element(By.ID, 'issue_assigned_to_id').click()

screenshot(redmine_gui)

# ignore

redmine_gui.execute_script("window.scrollTo(0, document.body.scrollHeight);")

screenshot(redmine_gui)

Clicking on "Create" creates the new issue report.

# ignore

redmine_gui.find_element(By.NAME, 'commit').click()

screenshot(redmine_gui)

Our bug has been assigned an issue number (#1 in that case). This issue number (also known as bug number, or problem report number) will be used to identify the specific issue from this point on in all communication between developers. Developers will know which issues they are working on; and in any change to the software, they will refer to the issue the change relates to.

Over time, issue databases can grow massively, especially for popular products with several users. As an example, consider the Mozilla Bugzilla issue tracker, collecting issue reports for the Firefox browser and other Mozilla products.

# ignore

from bookutils import quiz

quiz("How many issues have been reported over time in Mozilla Bugzilla?",

[

"More than ten thousand",

"More than a hundred thousand",

"More than a million",

"More than ten million"

], '370370367 // 123456789')

Quiz

Yes, it is that many! Look at the bug IDs in this recent screenshot from the Mozilla Bugzilla database:

# ignore

redmine_gui.get("https://bugzilla.mozilla.org/buglist.cgi?quicksearch=firefox")

# ignore

screenshot(redmine_gui)

Let us enter a few more reports into our issue tracker.

Managing Issues¶

Let us now switch sides and take the view of a developer whose job it is to actually handle all these issues. When our developers log in, the first thing they see is that there are a number of new issues that are all "open" – that is, in need to be addressed. (For a typical developer, this may well be the first task of the day.)

# ignore

redmine_gui.get(redmine_url + "/projects/debuggingbook")

screenshot(redmine_gui)

Clicking on "View all issues" shows us all issues reported so far.

# ignore

redmine_gui.get(redmine_url + '/projects/debuggingbook/issues')

redmine_gui.execute_script("window.scrollTo(0, document.body.scrollHeight);")

screenshot(redmine_gui)

Let us do some bug triaging here. Bug report #2 is not a bug – it is a feature request. We invoke its "actions" pop-up menu and mark it as "Feature".

# ignore

redmine_gui.get(redmine_url + "/issues/")

# ignore

redmine_gui.find_element(By.XPATH, "//tr[@id='issue-2']//a[@title='Actions']").click()

time.sleep(0.25)

# ignore

tracker_item = redmine_gui.find_element(By.XPATH,

"//div[@id='context-menu']//a[text()='Tracker']")

actions = webdriver.ActionChains(redmine_gui)

actions.move_to_element(tracker_item)

actions.perform()

screenshot(redmine_gui)

# ignore

redmine_gui.find_element(By.XPATH, "//div[@id='context-menu']//a[text()='Feature']").click()

The same applies to bugs #3 and #4 (missing PDF) and #6 (no support for C++). We mark them as such as well.

# ignore

def mark_tracker(issue: int, tracker: str) -> None:

redmine_gui.get(redmine_url + "/issues/")

redmine_gui.find_element(By.XPATH,

f"//tr[@id='issue-{str(issue)}']//a[@title='Actions']").click()

time.sleep(0.25)

tracker_item = redmine_gui.find_element(By.XPATH,

"//div[@id='context-menu']//a[text()='Tracker']")

actions = webdriver.ActionChains(redmine_gui)

actions.move_to_element(tracker_item)

actions.perform()

time.sleep(0.25)

redmine_gui.find_element(By.XPATH,

f"//div[@id='context-menu']//a[text()='{tracker}']").click()

# ignore

mark_tracker(3, "Feature")

mark_tracker(4, "Feature")

mark_tracker(6, "Feature")

# ignore

redmine_gui.get(redmine_url + "/issues/")

redmine_gui.execute_script("window.scrollTo(0, document.body.scrollHeight);")

screenshot(redmine_gui)

The fact that we marked these issues as "feature requests" does not mean that they will not be worked on – on the contrary, a feature requested by management can have an even higher priority than a bug. Right now, though, we will give our first priority to the bugs listed.

Assigning Priorities¶

After we have decided the priority for individual bugs, we can make this decision explicit by assigning a priority to each bug. This allows our co-developers to see which things are the most pressing to work on.

Let us assume we have an important customer for whom fixing issue #1 is important. Through the context menu, we can assign issue #1 a priority of "Urgent".

# ignore

redmine_gui.get(redmine_url + "/issues/")

# ignore

redmine_gui.find_element(By.XPATH, "//tr[@id='issue-1']//a[@title='Actions']").click()

time.sleep(0.25)

# ignore

priority_item = redmine_gui.find_element(By.XPATH, "//div[@id='context-menu']//a[text()='Priority']")

actions = webdriver.ActionChains(redmine_gui)

actions.move_to_element(priority_item)

actions.perform()

screenshot(redmine_gui)

# ignore

redmine_gui.find_element(By.XPATH, "//div[@id='context-menu']//a[text()='Urgent']").click()

We see that issue #1 is now listed as urgent.

# ignore

redmine_gui.get(redmine_url + "/issues/")

redmine_gui.execute_script("window.scrollTo(0, document.body.scrollHeight);")

screenshot(redmine_gui)

On top of priority, some issue trackers also allow assigning a severity to an issue, describing the impact of the bug:

- Blocker (also known as Showstopper): Blocks development and/or testing, for instance by breaking build processes.

- Critical: Application crash. Loss of data.

- Major: Loss of function.

- Minor: Incomplete function.

- Trivial: Minor issues in user interfaces and documentation.

- Enhancement: Request of a new feature or an improvement in an existing one.

The severity would be an important factor in determining the priority of an issue.

Assigning Issues¶

So far, all the listed bugs are "unassigned", which means that there is no developer who is currently working on them. Let us assign the "urgent" issue #1 to ourselves, such that we have something to do.

# ignore

redmine_gui.get(redmine_url + "/issues/")

# ignore

redmine_gui.find_element(By.XPATH, "//tr[@id='issue-1']//a[@title='Actions']").click()

time.sleep(0.25)

# ignore

assignee_item = redmine_gui.find_element(By.XPATH,

"//div[@id='context-menu']//a[text()='Assignee']")

actions = webdriver.ActionChains(redmine_gui)

actions.move_to_element(assignee_item)

actions.perform()

screenshot(redmine_gui)

By choosing the Actions menu, clicking on Assignee, and then << me >>, we can assign the issue to ourselves.

# ignore

redmine_gui.find_element(By.XPATH, "//div[@id='context-menu']//a[text()='<< me >>']").click()

screenshot(redmine_gui)

Of course, we could also go and assign the issue to other developers – depending on their competence and current workload. Very clearly, the ability to assign issues to individuals is a feature for managers.

Resolving Issues¶

Let us switch perspectives again, and now take a developer's role – that is, we now work on the issues assigned to us. We get these by clicking on "Issues assigned to me":

# ignore

redmine_gui.get(redmine_url + "/projects/debuggingbook/issues?query_id=1")

screenshot(redmine_gui)

By clicking on the issue number, we can see all details about the issue.

# ignore

redmine_gui.get(redmine_url + "/issues/1")

screenshot(redmine_gui)

We can inspect all features of the issue, including its history.

# ignore

redmine_gui.execute_script("window.scrollTo(0, document.body.scrollHeight);")

screenshot(redmine_gui)

Let us assume that we do have everything in hand we need to fix the bug. (Including a Nokia Communicator device for testing, that is.) This will take some time, during which we won't need our bug database.

Let us now assume that we actually have fixed the bug. This means that we have to go back to our bug database such that we can mark the bug as resolved. For this, we open the issue again and click on "Edit", and then change the status from "New" to "Resolved".

# ignore

redmine_gui.get(redmine_url + "/issues/1/edit")

redmine_gui.find_element(By.ID, "issue_status_id").click()

# ignore

redmine_gui.find_element(By.XPATH, "//option[text()='Resolved']").click()

screenshot(redmine_gui)

At the bottom, we can add more notes.

# ignore

redmine_gui.execute_script("window.scrollTo(0, document.body.scrollHeight);")

issue_notes = redmine_gui.find_element(By.ID, "issue_notes")

issue_notes.send_keys("Will only work for Nokia Communicator Rev B and later; "

"Rev A is still unsupported")

screenshot(redmine_gui)

After clicking on "Submit", we are done. Time for the next bug to fix!

# ignore

redmine_gui.find_element(By.NAME, "commit").click()

screenshot(redmine_gui)

The Life Cycle of an Issue¶

We have successfully reported an issue (as some third party), assigned it (as a manager), and resolved it (as a developer). Great! However, the steps we have been going through are just one way an issue might be handled.

Resolutions¶

First, an issue can have multiple resolutions besides being fixed. Typical resolutions include the following:

FIXED¶

A fix for this issue is made and committed. This is the resolution we have seen for the "Nokia Communicator" bug #1, above.

INVALID¶

The problem described is not an issue. This is what happens to entries in the issue database that actually do not describe an issue, or that do not provide sufficient information to address it.

WONTFIX¶

The issue described is indeed an issue, but will never be fixed. This is a decision of which features (and fixes!) are part of the product, and which ones are not. Our listing of hypothetical issues, above, has an entry complaining that the book "does not work with Python 2.7 or earlier". This will not be fixed.

DUPLICATE¶

The issue is a duplicate of an existing issue. In our listing of hypothetic issues, we have two issues reporting problems with PDF exports. By making one of these a duplicate of the other. we can ensure that both will be fixed (and checked) at the same time.

If your product has several users, your issue database will have several duplicates, as multiple users will stumble across the same bugs. Some developers consider such duplicates as a burden, as identifying duplicates takes time. However, the study by Bettenburg et al.~\cite{Bettenburg2008} points out that such duplicates have their value, too. One developer is quoted as

Duplicates are not really problems. They often add useful information. That this information were filed under a new report is not ideal thought.

WORKSFORME¶

The developer could not reproduce the issue, and the code provided no hints on why such a behavior might occur. Such issues are often reopened when more information becomes available.

An Issue Life Cycle¶

With this in mind, we can sketch the individual states an issue report goes through: After submission (NEW), the report is assigned to a developer (ASSIGNED), and then resolved (RESOLVED) with one of the resolutions listed above.

# ignore

from Intro_Debugging import graph # minor dependency

# ignore

from IPython.display import display

# ignore

life_cycle = graph()

life_cycle.attr(rankdir='TB')

life_cycle.node('New', label="<<b>NEW</b>>", penwidth='2.0')

life_cycle.node('Assigned', label="<<b>ASSIGNED</b>>")

with life_cycle.subgraph() as res:

res.attr(rank='same')

res.node('Resolved', label="<<b>RESOLVED</b>>", penwidth='2.0')

res.node('Resolution',

shape='plain',

fillcolor='white',

label="""<<b>Resolution:</b> One of<br align="left"/>

• FIXED<br align="left"/>

• INVALID<br align="left"/>

• DUPLICATE<br align="left"/>

• WONTFIX<br align="left"/>

• WORKSFORME<br align="left"/>

>""")

res.node('Reopened', label="<<b>REOPENED</b>>", style='invis')

life_cycle.edge('New', 'Assigned', label=r"Assigned\lto developer")

life_cycle.edge('Assigned', 'Resolved', label="Developer has fixed bug")

life_cycle.edge('Resolution', 'Resolved', arrowhead='none', style='dashed')

life_cycle

Unfortunately, software development is more complicated than that. There are many things that can happen while an issue is being worked on.

- When an issue report comes in, it may be resolved as "invalid" or "duplicate" before even being assigned to a developer.

- The developer assigned to an issue might change.

- Fixes suggested by developers might be subject to quality assurance, to ensure that they

- fix the error under all circumstances

- do not introduce new errors

- Issues may be reopened if the fix is inadequate or new information becomes available.

With this in mind, the states an issue report can go through become a bit more complex. Note how issues start in a state of "UNCONFIRMED" as long as nobody has assessed them, and how issues are marked as "CLOSED" (the final state) only after the resolution has been checked by quality assurance.

# ignore

life_cycle.node('Unconfirmed', label="<<b>UNCONFIRMED</b>>", penwidth='2.0')

# life_cycle.node('Verified', label="<<b>VERIFIED</b>>")

life_cycle.node('Closed', label="<<b>CLOSED</b>>", penwidth='2.0')

life_cycle.node('Reopened', label="<<b>REOPENED</b>>", style='filled')

life_cycle.node('New', label="<<b>NEW</b>>", penwidth='1.0')

life_cycle.edge('Unconfirmed', 'New', label="Confirmed as \"new\"")

life_cycle.edge('Unconfirmed', 'Closed', label=r"Resolved\las \"invalid\"\lor \"duplicate\"")

life_cycle.edge('Assigned', 'New', label="Unassigned")

life_cycle.edge('Resolved', 'Closed', label=r"Quality Assurance\lconfirms fix")

life_cycle.edge('Resolved', 'Reopened', label=r"Quality Assurance\lnot satisfied")

life_cycle.edge('Reopened', 'Assigned', label=r"Assigned\lto developer")

# life_cycle.edge('Verified', 'Closed', label="Bug is closed")

life_cycle.edge('Closed', 'Reopened', label=r"Bug is\lreopened")

life_cycle

Such states (and the implied transitions between them) can be found in any issue tracking system. The actual names may vary (ASSIGNED is also known as IN_PROGRESS; instead of or besides CLOSED, one can also have VERIFIED), but their meanings are always the same.

Whatever the states and resolutions are called (and they can be configured, anyway), the important thing is that they be used consistently for your project and in your organization. This is how at any point, any team member can see

- what the most pressing tasks are;

- what he or she should be working on; and

- what the overall state of the project is.

The latter point is particularly important, since an issue tracker need not only be used for tracking bugs, but also for tracking and assigning features – notably features that have been decided to be part of the product. Hence, if you want to have some new feature implemented, you can mark it as a "NEW" issue, break it into subfeatures, also all marked as "NEW", and then assign the associated subtasks to individual developers. The feature would then be ready when all subtasks are completed as "FIXED".

This way, you can organize an entire software project through the issue tracker. Start with the first issue "The product is missing", and then keep on defining and assigning subtasks; when all are resolved, the product will be ready. Since some issue trackers (including Redmine) also allow developers to report how far they got with resolving an issue (say, "10%", "50%", or "90%"), you can even estimate how long resolving the open issues will take.

Over time, an issue database not only becomes an important tool for managing bug fixing and organizing software development, it also holds a trove of data about where, what, and why specific issues were addressed. In the next chapter, we will explore how to mine and evaluate such data.

# ignore

# We're done, so we shut down Redmine and associated processes

redmine_process.terminate()

redmine_gui.close()

# ignore

os.system("pkill ruby");

Synopsis¶

This chapter provides no functionality that could be used by third-party code.

Lessons Learned¶

- In an organization, fixing bugs and issues is best organized through an issue tracker.

- An issue tracker allows issue reports

- to be collected;

- to assign them with a state (from NEW to CLOSED) in its life cycle;

- to be assigned to developers; and

- to assign them with a resolution (including FIXED, DUPLICATE, and WORKSFORME).

- Issue trackers can organize the entire software development, including new products and features.

Next Steps¶

- The chapter on mining version histories describes how to mine and analyze the data from bug and version databases.

Background¶

The survey by Bettenburg et al. \cite{Bettenburg2008} is the seminal work on how developers make use of bug reports. The study by Bertram et al. \cite{Bertram2010} highlights how issue trackers are not just databases, but "a focal point for communication and coordination for many stakeholders within and beyond the software team."

The report by \cite{Glerum2009} provides details on how Windows Error Reporting automates the processing of error reports coming from an installed base of a billion machines, providing impressive numbers on bugs in the wild.

Research on bug databases has very much focused on how to make predictions such as automatically identifying duplicates \cite{Wang2008}, possible bug locations \cite{Kim2013}, or automatically assigning issues to developers \cite{Anvik2006}. Herzig et al. \cite{Herzig2013}, however point out that much of the information in bug database is not classified properly enough, for instance to reliably distinguish between bugs and features.

Mozilla's Bugzilla bug database is one of the largest publicly available issue databases. It is worth browsing for real-world bug reports, and also contains important articles on how to write and use bug reports.